Huế and Da Nang: Reflections on a proxy war

On this morning, we took a short flight from Saigon’s airport to Huế. The family was annoyed the tour representative showed up late, Tam was worried we got scammed. But no, apparently 530 AM was early for him too. He handed us our flight info and told us we’d be meeting another person at the next airport.

When we landed in Huế, we deplaned directly onto the runway and boarded a bus that drove us about 200 feet away from where we once stood. We could have walked in the time we waited for the bus to load… But I get it, safety first. The Huế airport had one building; arrivals and departures shared the same building. It took me 3 minutes to walk from one end to the other in search of a toilet.

Tam was already impatient at this point. The first representative didn’t meet us at the Saigon airport on time, and the tour guide in Huế was late. He couldn’t miss us with the highlighter green hats we were given. One bonus to Vietnam is that everywhere has cà phê sữa đá (iced coffee). That kept Tam occupied until our tour guide did arrive.

We drove to our next destination on a two-lane road. Many of the houses in Vietnam are long and deep, so you can see into the home from just the front, an entire life revealed in a 5-second drive-by. There were small farms and fields as far as the eye could see. As we approached the center of Huế, the neighborhoods became denser and the roads became wider to accommodate cars.

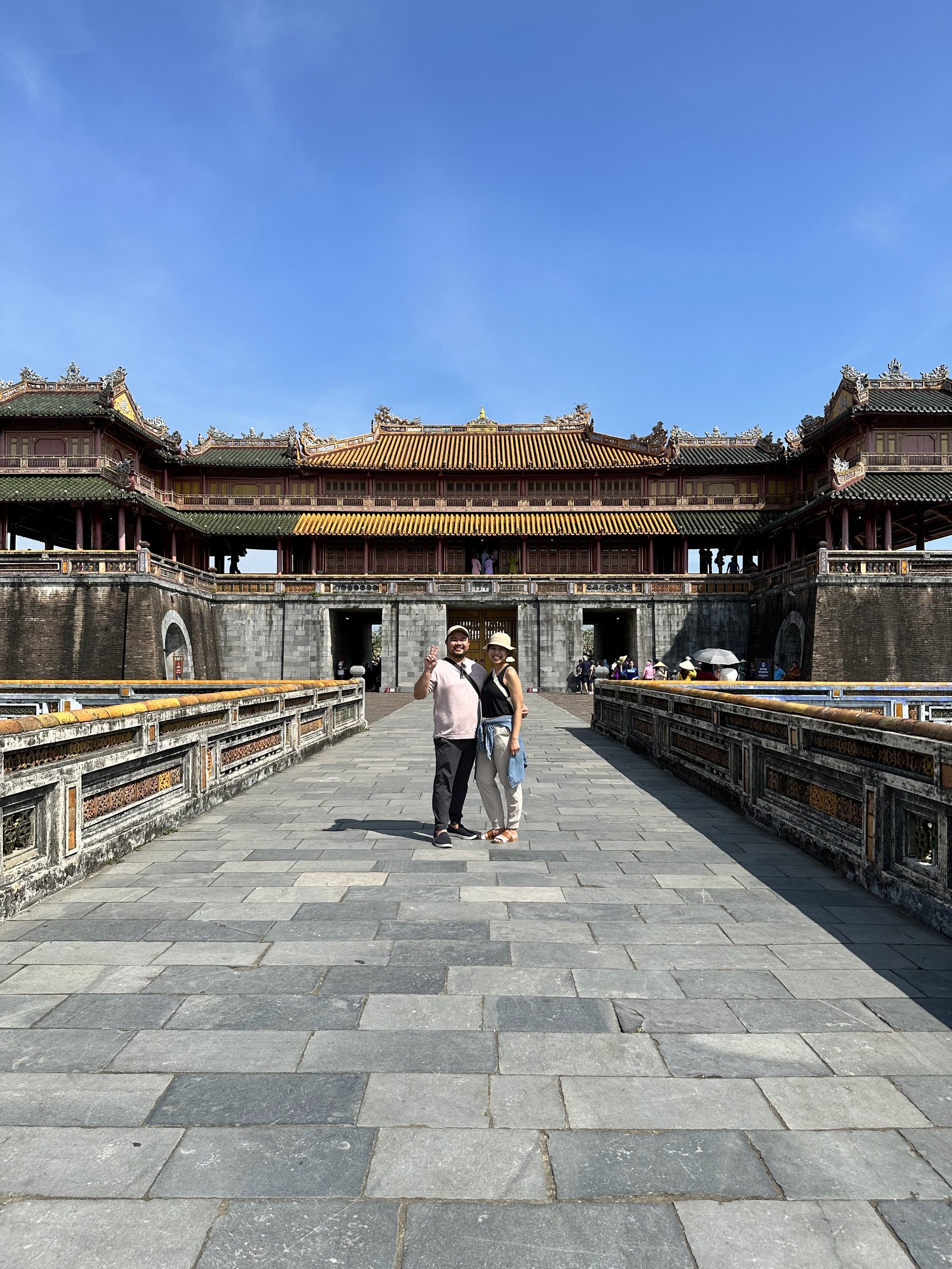

After breakfast, we visited the Imperial City of Huế, home of the Nguyen dynasty from 1803 to its end in 1945. There were a lot of Vietnamese tour guides speaking different languages: French, English, Japanese, you name it. Our own tour guide only spoke Vietnamese, and with a central Vietnam intonation, so Tam could only understand parts of his tour. Tam translated as best as he could, but all I could do was observe and supplement the info with anything written in English. Tam’s parents definitely got a lot more from it.

The once the home of the Nguyen dynasty now had the royal family interred on its grounds. I also learned that this city was damaged and bombed during the Vietnam War. Tam and I discussed how the Vietnam War was just one of the conflicts in the West’s proxy war against communist Russia and China. It’s a time period that I didn’t learn much about in school. Despite being in AP US History, the textbooks conveniently stopped at World War II, the last time we “won”.

I don’t know much about these wars at all.

The era of McCarthyism and the Red Scare made communism a convenient enemy to the free and democratic America. But as Tam and I interrogate this history, many of those anti-communist conflicts were sneaky ways for the US to assert its global dominance as Europe’s stronghold on the world and its former colonies loosened. I learned a proxy war is one where two (or more) conflicting parties wage war by using other states or countries, like Northern Vietnam/Russia/China vs. Southern Vietnam/US/West.

In the US, we have been taught that communism is bad because the government can own and seize the means of production. The government controlling the economy means it has control over its people. I suspect this experience is what lead someone like Ayn Rand to write The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, after her own parents’ business was seized by the government and they fled to the use. One would say there’s no freedom in this.

In the US, we are free to work and earn money as we choose, through personal enterprise or by working for another. We have the freedom to make choices, but the menu of choices can be limited. Are we free when our healthcare is tied to our employer, trapping people to unfavorable working conditions and wages? Are we really free when our incomes can’t afford basic necessities like food? Housing? Clean water? The government doesn’t own the means of production and has not seized any businesses, yet I’d argue that there are oppressive conditions in this setup.

Communist countries don’t select their leaders through a truly free and public vote… Yet there are citizens in the US who live in gerrymandered counties, where their representatives don’t represent the majority. They’re unable to exercise their right to vote easily and without obstacles. This leads to a disenfranchised population, too tired and unwilling to participate in a government made for and by the people. How is this different?

Power is insidious and can take on many disguises. Whether it’s communism or capitalist democracy, oppression still exists. I find that we get so caught up in the word, that we don’t interrogate the actions executed on behalf of “freedom”, “democracy”, or “for our country.” It’s easy to point at another country and cry suppression of free expression, while in our own country we persecute and kill people for living authentically. Eliminating oppression is an active choice, one that doesn’t come easily when people are fighting to survive.

Once the US retreated from Saigon, Vietnam ran re-education camps on people who sided with the US. In turn, the US imposed decades-long trade sanctions on Vietnam, undoubtedly similar to other communist countries of the time. Because of this, a western dollar can buy luxury in a country conquered once by colonialism and again by global capitalism… Many goods in America are produced in other countries because it’s cheap and the resources plentiful, a result of excluding them from global free trade. The prices never encompass the historical costs.

What harm have we caused to achieve our “goals” as a country?

All this to say that in the Imperial City of Huế I felt grief. What was lost to war? To colonization? How many dreams were lost? Was this conflict necessary? In this way? What purpose did it serve? It took interested Europeans to begin the city’s restoration, but it would never be the same palace nor the same country it was before the war.

It did make me wonder what Vietnamese people call the Vietnam War? What are their lessons from it? What’s their narrative? There’s power in controlling the narrative. Free speech is vital to democratic countries; its suppression is essential for authoritarian ones. This is something I’ll have to research later. The US education system did not want me to learn about post-WWII history.

Its absence in my curriculum is a kind of censorship.

We eventually left Huế to go to Da Nang, a beach city in central Vietnam. These roads were surprisingly smooth, some of them probably didn’t exist five years ago. Some of the stops we made were clearly made to cater to our tourist dollars. The cà phê sữa đá that Uncle Dad bought us every morning cost less than 20 cents. The tour itself cost about $2100 USD per person, but our tour guide and driver likely made a very small fraction of it. They might make more if they spoke Western languages, like the others we had seen at the Imperial Palace.

The drive was beautiful and peaceful. We even stopped at a temple. When I wasn’t reading, I used the drive to reconcile the safety and wealth that the US has provided me with the harm it has caused to maintain it. Few things are as human as choosing how we hold conflicting truths equal at the same time. You can interrogate it or ignore it, different choices on the path of survival.

At the temple, I saw plants I hadn’t seen before, heard new animals, and saw what I thought was a squirrel. Despite our language barrier, the tour guide used his hands and some sound effects to tell me that these flowers exploded. We laughed, explosions are easy to communicate in any language.

The evening in Da Nang was pretty chill. We watched the sunset, ate dinner, and explored a night market before heading back to rest.